The situation in Poland after the Third Partition in 1795 was undoubtably grim. Both her efforts at constitutional reform and armed uprising had failed miserably. King Stanisław II Augustus had been forced to abdicate his throne and patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko had been defeated in battle and thrown into a St. Petersburg prison, presumably to languish there for the rest of his days.

Poland’s hostile neighbours – Russia, Prussia, and Austria – had carved her up piecemeal, and privately agreed to wipe the memory of the “existence of a Polish kingdom” from the face of history, in a joint memorandum published not soon after the Commonwealth’s final dismemberment.

Nevertheless, “Poland was not yet lost,” in the immortal words of poet-soldier Józef Wybicki’s “Song of the Polish Legions in Italy,” which would one day be adopted as Poland’s national anthem. Joining Wybicki under French command in northern Italy were General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (famously invoked in the anthem), and several other patriots and veterans of the recent wars in defence of the late Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Although they were not all ideologically aligned with Revolutionary France or its Napoleonic successor, the Poles and French now shared a common enemy in the Partitioning Powers. Ironically, the very same Poles who had performed admirably, but ultimately failed to defend their own country against the might of Austria, Russia, and Prussia, would now serve as some of the most loyal and capable soldiers of the French Grande Armée against those very same empires for the next 20 years.

Even within Russia, however, the situation would ease slightly with the death of Empress Catherine II in 1796. She would be succeeded by her son, Paul, who deeply resented his mother and set about reversing several of her policies and ambitions.

He personally befriended Kościuszko and released him from prison, after which the Polish patriot would escape to exile in Western Europe and America, ultimately living out his last days in Switzerland before his passing in 1817. Paul would also befriend ex-King Stanisław, inviting him to live in St. Petersburg until his death in 1798, at which point Paul would offer him a state funeral, himself leading the procession of mourners.

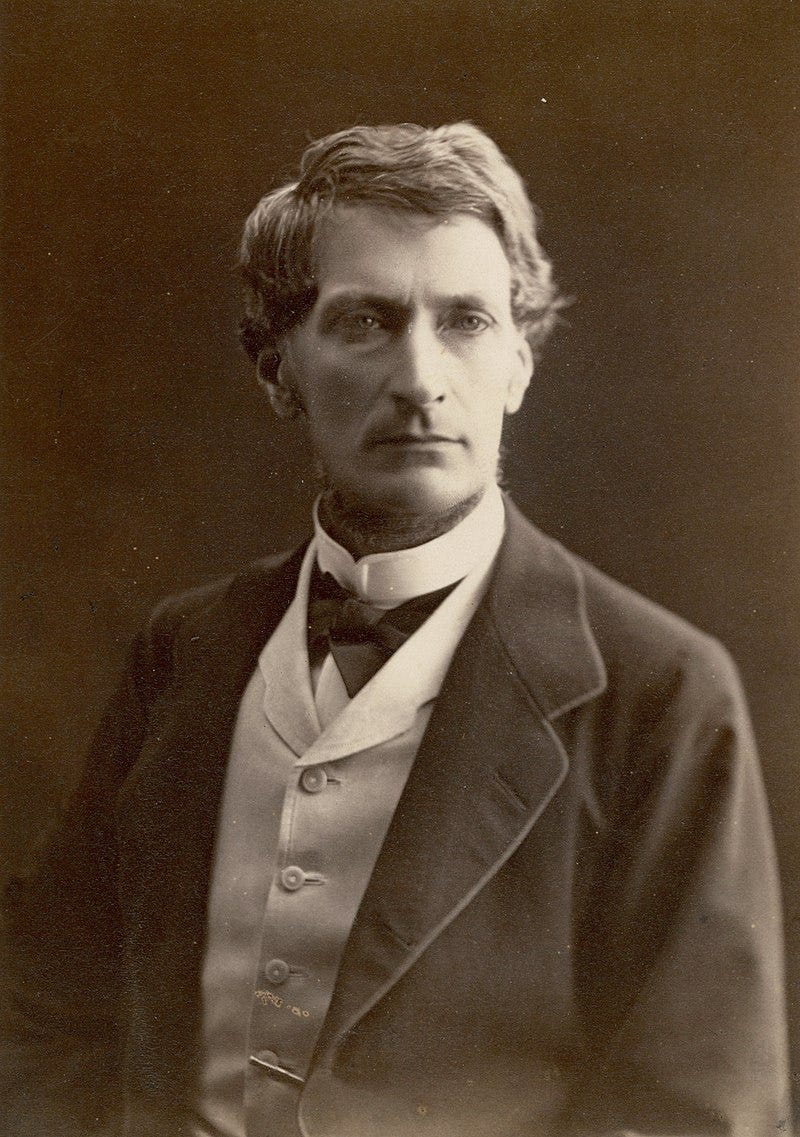

Even after Paul’s deposition and assassination in 1801, his son, Alexander, made fast friends with Polish noble and patriot Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, first cousin of King Stanisław and son of the former patriarch of the late Commonwealth’s Familia faction of the same name. Czartoryski was an integral member of the inner circle of Alexander’s early reign, which was intently devoted to schemes of Russian constitutional reform.

Czartoryski would also serve as Alexander’s foreign minister from 1804-06, and even after his subsequent fall from power, would remain the most influential Polish statesman in Russia, Poland, or indeed in Europe for the next several decades – a veritable “uncrowned King of Poland.”

Czartoryski notwithstanding, however, most Polish patriots aligned their national interests and aspirations with Napoleonic France. Although the French Emperor did not always have the Poles’ best interests at heart, Napoleon was largely revered by Polish patriots, who saw in him Poland’s best hope to defeat her enemies and restore her rightful place among the great states of Europe.

Indeed, Napoleon was a conqueror of almost incomparable pedigree in European history, crushing all three of Austria, Prussia, and Russia on the field of battle, and trying – with varying degrees of success – to keep British influence on the Continent at bay.

In addition to their early exploits in northern Italy, Polish legions would serve with distinction under the French banner in several of Napoleon’s great campaigns. Indeed, much like the Winged Hussars of old, the Grande Armée’s Polish cavalry units would gain legendary status among the Poles, French, and allies and enemies alike. Perhaps most famous was the incredible victory of 125 Polish chevau-légers (light cavalry) against 9,000 entrenched Spanish infantry units at Somosierra in 1808.

Much like the later celebrated Polish victory at Monte Cassino in the Second World War, the success of the Poles in winning the mountain pass cleared the road to allied French troops to enter nearby Madrid. Closer to home, the Poles would join Napoleon following his crushing defeat of the Prussian army at Jena-Auerstadt in 1806, allowing the Poles to symbolically march victorious onto their own lost territory.

Following Napoleon’s momentous meeting with Tsar Alexander at Tilsit, in 1807, and their resulting treaty splitting the European Continent between them, Poland west of the Bug River fell into the French sphere of influence, and Napoleon soon reorganized the bulk of the original Prussian Partition into a new “Duchy of Warsaw.”

Although effectively a French client state, its very existence was living proof that Polish dreams of restoring national independence were indeed “not yet lost,” and several Poles who had served the Commonwealth in her last days were appointed to leadership positions within the Duchy.

Most notably, Prince Józef Poniatowski, nephew of the late King, was appointed commander-in-chief of the army, while Stanisław Małachowski, Marshal (speaker) of the last Polish-Lithuanian Sejm, was chosen to head its government. Meanwhile, Frederick Augustus of Saxony, grandson of the Commonwealth’s penultimate monarch, was chosen to now serve as the hereditary “Duke of Warsaw.”

Following Napoleon’s crushing of the Austrians at Wagram and the subsequent Treaty of Schönbrunn (1809), sections of the Austrian Partition, including Kraków, were further tacked onto the Duchy of Warsaw, which now encompassed most of the traditional Polish heartland of Mazovia, Wielkopolska, and Małopolska.

When Napoleon made his fateful decision to invade Russia in 1812, Poles were overrepresented in his invasion force, constituting almost 100,000 of the 600,000-strong Grande Armée, Napoleon’s largest non-French contingent. He even framed this conflict as his “Second Polish War” (with his “first” being the conflict that preceded Tilsit), and made vague promises to the Poles about the further restoration of their lost country.

Although Napoleon’s intentions were not entirely sincere, it was not lost on his Polish soldiers that the opening of the war involved crossing the traditional border of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and that victory could present a unique opportunity for the Poles to liberate all former territories of the Commonwealth.

Poles would play pivotal roles in both Napoleon’s initial invasion – notably at Smolensk and Borodino – as well as rear-guarding his disastrous retreat – notably at Vyazma, Berezina, and Leipzig – losing a jarring 80% of the Polish force that had initially crossed the Lithuanian frontier in June 1812.

Perhaps emblematic was Prince Poniatowski, promoted during the Battle of Leipzig (1813) to the prestigious rank of “Marshal” of the French Empire – the only non-Frenchman to ever earn the title – three days before his death. Although offered the possibility of amnesty by the Tsar, Poniatowski was loyal to the end – even if to a fault – drowning in a river after the French had blown up the bridge they had crossed to make their retreat.

Such was the appreciation shown towards Polish loyalty and bravery after 20 years of support for the French cause. Indeed, although the actions of the Polish legions under the French banner would inspire countless later generations of Polish patriots, their efforts at the time were largely in vain, and Poland would subsequently be re-Partitioned at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Nonetheless, the infamous “Polish Question” would remain a controversial issue for European statesmen and diplomats for the entire course of the 19th century. Fundamentally, the dilemma was that Poland’s long and proud history of independent statehood and the sheer size of her population and territory made subjugation of the Poles by any one of the three Partitioning Powers extremely difficult.

In many ways, Poland was the glaring blind spot in the Congress of the Vienna’s ultimate project to build a lasting post-war peace based on principles of legitimacy and stability. The Partitions of Poland had been an ostensibly illegitimate act against an old and storied European state, and effectively sealing their approval and sentencing the Poles to perpetual frustration and resentment of their lost country was a recipe for turning erstwhile loyal supporters of the post-Vienna Conservative Order into potential revolutionaries.

Nonetheless, a restoration of Poland to her 1772 borders was unthinkable to the leaders of the Congress. The late Commonwealth period had demonstrated an apparent inability of the Poles to manage their own affairs or to effectively defend Poland’s borders without the aid of a stronger foreign protector, such as France or Britain, whose geopolitical interests might not necessarily align with those of Austria, Russia, or Prussia.

Furthermore, the collaboration of many Polish patriots with the now-defeated Napoleonic regime was not taken kindly to by the three empires, who had together joined Britain in the final victorious coalition against the despised French Emperor. As such, it was very unlikely that the Poles would receive a favourable treatment in the final European settlement at Vienna.

Perhaps fittingly, it would indeed be the Polish Question that caused the most vociferous disagreement between the Great Powers at the Congress. As both Poland and Saxony had allied with Napoleon throughout the preceding period, the Russian and Prussian delegations proposed that they should respectively annex the entirety of both nations into their empires.

Considering that Tsar Alexander was sympathetic to Poland and had brought his friend, Polish noble and patriot Adam Czartoryski with him as a delegate, this might not have been such a bad result, as it would have offered the later possibility of Polish independence from Russia under a united front. Nonetheless, the British and Austrian delegations rejected this outright, as they argued it would make Russia and Prussia too powerful.

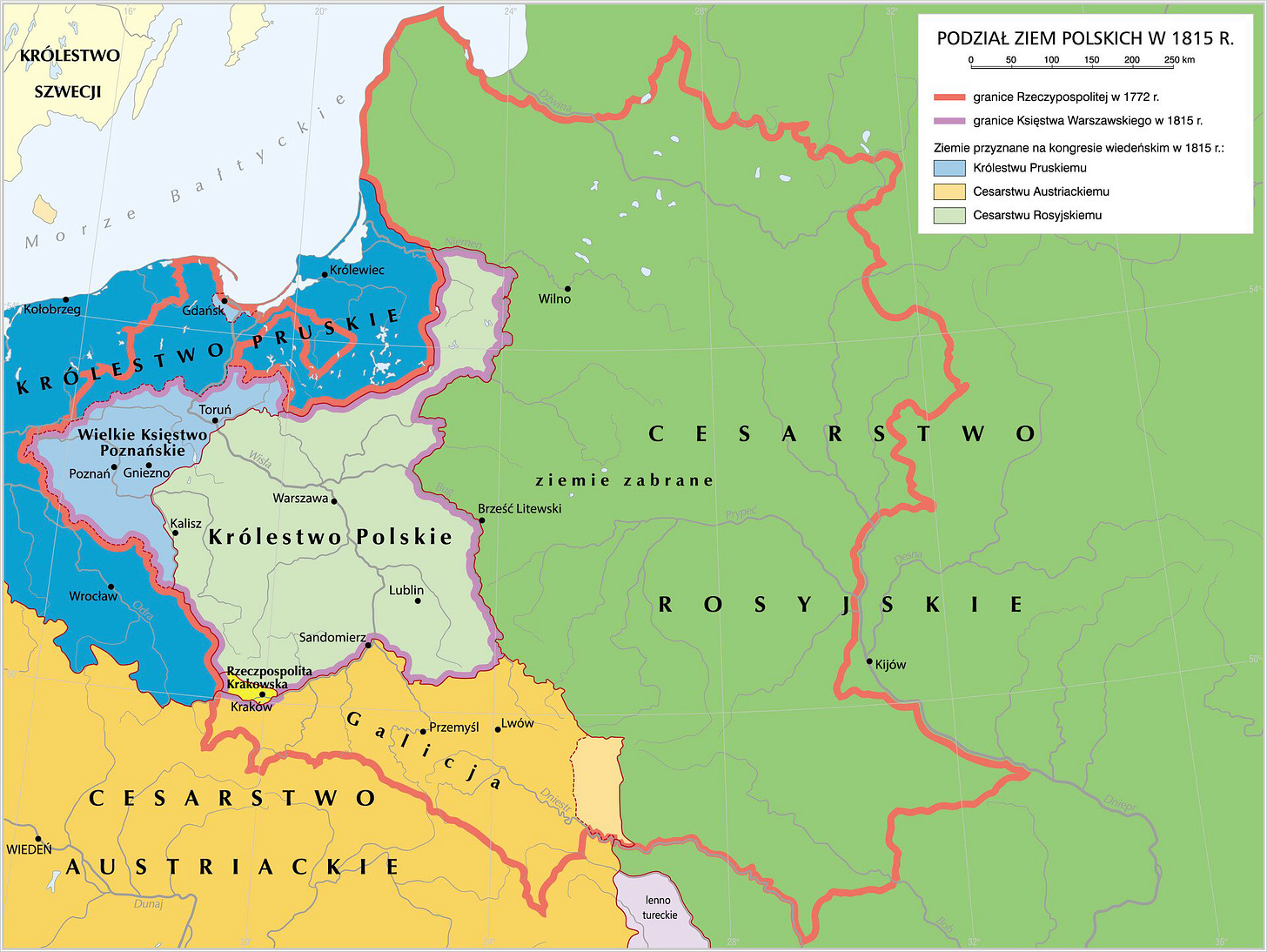

The dispute nearly resulted in a renewed war between an Anglo-Austro-French coalition and their Russian and Prussian counterparts. Ultimately, the parties would reach a compromise in which the Prussians would annex roughly half of Saxony, while Alexander would absorb most of the former Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw, now rechristened the “Kingdom of Poland,” with the Russian Tsar established as her King.

The “Congress Kingdom,” as it later came to be known, covered most of the Polish region of Mazovia and began its life as a constitutional monarchy and genuinely autonomous polity. This was especially true under the reign of Alexander I, who was largely sympathetic to Poland and allowed the Poles to effectively run their own army and government administration from Warsaw.

Although these freedoms would be severely curtailed following the Polish Uprisings of 1830 and 1863, there is an argument to be made that the Congress Kingdom was, at least for a brief time, the most authentically “Polish” successor state to the Commonwealth.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the Russian Partition was formally incorporated into the Russian Empire as the “Western Gubernias,” effectively treated as long lost lands of Kievan Rus’ now finally “reunited” with their Great Russian brethren from Moscow. Although a Polish element in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine persisted from the beginning to end of the Partition period, efforts at Russification over the course of the century fundamentally changed the character of many of these regions, which had been integral parts of the Commonwealth since its inception.

Conversely, the Wielkopolskan slice of the former Duchy of Warsaw was now reincorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia, granted autonomous status as the “Grand Duchy of Posen.” At least for the first half of the 19th century, Posen (German for Poznań) was likely the best section of the Partitions for Poles to live under. Not only did the Poles have relative political freedom – and until 1830, a Polish Viceroy in Antoni Radziwiłł – but with Prussian rule also came the blessings of economic prosperity and effective civil administration.

Nonetheless, the political freedoms afforded in Posen would soon be curtailed, first after the 1830 Uprising in the neighbouring Congress Kingdom, and then once more after Posen’s contribution to the European revolutions of 1848. Worse still were the aggressive campaigns of Germanization initiated after German Unification in 1871 by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck as part of his wider Kulturkampf against Catholics and ethnic minorities in the new Imperial Germany.

Remarkably, the Poles of Posen would successfully resist Bismarck’s efforts and solidify the distinctly Polish and Catholic character of the region. Beyond Posen, a Polish element would survive in several other regions of the former Commonwealth that were directly incorporated into Prussia and the German Empire. Most notable were the Poles (and Kashubians) in West Prussia and Pomerania, and the Poles of Upper Silesia and Mazuria (East Prussia).

Meanwhile, the near-entirety of the Austrian Partition – which covered the lands of Małopolska and Red Ruthenia – continued its life rechristened as the “Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,” an homage to a medieval west Ukrainian state to which the Habsburgs claimed legitimate succession. Notwithstanding several historic minorities of the region, such as Jews and Armenians, the province was unofficially split along ethnic lines into two halves, roughly along the San River, with the Poles predominating in “West Galicia” and Ukrainians in “East Galicia.”

Perhaps fittingly, the Polish city of Lwów in East Galicia was chosen by the Habsburgs to serve as the administrative capital officially under the neutral German name of “Lemberg.” As Galicia was somewhat remote from the rest of the empire, being north of the Carpathian Mountains, it developed a great degree of autonomy over the course of the century.

The Austrians were initially very suspicious of the traditional Polish elites of Galicia, going as far as to incite a violent peasant revolt (jacquerie) against the szlachta of the region in 1846. However, after the destabilizing revolutions of 1848 and Vienna’s granting of autonomy to Hungary in 1867, the Polish nobility of Galicia were co-opted by the Habsburgs to govern Galicia as Viceroys and local administrators for the rest of the period.

Remarkably, the Polish-Galician nobility would so distinguish themselves in these roles that they would not only serve as governors within Galicia, but as Ministers (and remarkably even two Prime Ministers) within the Imperial Austrian cabinet in Vienna.

Most notable among these were: Agenor Romuald Gołuchowski (père), Viceroy of Galicia (1849-59, 1866-67, 1871-75) and Austrian Interior Minister (1859-60); Alfred Józef Potocki, Viceroy of Galicia (1875-83) and Austrian Prime Minister (1870-71); Agenor Maria Gołuchowski (fils), Austrian Foreign Minister (1895-1906); and Kazimierz Feliks Badeni, Viceroy of Galicia (1888-95) and Austrian Prime Minister (1895-97).

In stark contrast to the repressive regimes of Prussia and Russia, Austrian Galicia was remarkably tolerant to its subjects, such that Lemberg (Lwów/Lviv) became a hotbed for both the Polish and Ukrainian national movements in the late 19th century.

Finally, the most exceptional Polish territory of the Partition era was the “Republic of Kraków,” allowed to exist as a city-state at the nexus of the three empires prior to its annexation into Austrian Galicia following a failed uprising in 1846. Much like in the rest of Galicia, Habsburg rule in Kraków would be relatively benign, and the former royal capital of Poland would carry on its life as a lively centre of Polish culture and thought throughout the entire period.

One of the most distinct features of the Polish nation since the Partition period has been its exceptionally large émigré community, sometimes referred to as “Polonia” (Latin for Poland). To this day, there are almost half as many Poles living abroad as within the Polish Republic itself.

The extent to which these Polish émigrés have maintained a sense of Polish identity in their new contexts is a complex subject, and involves factors including their class origins (Poles of peasant origin did not always identify with traditional noble-centric narratives of Polish history), competing ethnic or religious identities (Polish Jews, mixed Polish-Ukrainians or Polish-Lithuanians), whether their motivation to emigrate was more for political or economic reasons (political émigrés were often more motivated to actively preserve their Polish culture), assimilation pressures in their new country, how many generations their family has been removed from living in Poland, or the particular wave in which their family emigrated.

The first notable wave of Polish emigration occurred following the 1830 Uprising against the Russian Empire, with most Polish émigrés fleeing to France and Britain. Towards the end of the 19th century, the United States and Canada would also grow into popular destinations for emigration, as would more remote places such as Australia and Argentina, although many of these would be economic migrants, fleeing the hopeless poverty of Russian Poland and Austrian Galicia.

Two of the most recent waves of Polish emigration occurred in the 1940s-50s, following the displacements of the Second World War, and in the 1980s-90s, coinciding with the decline and ultimate collapse of Communist Poland. Even today, Chicago and London remain two of the largest Polish centres in the world outside of Poland, and the émigré community has often offered political or economic assistance to the Polish national cause in times of need, including in the rebirth of Poland after the First World War or in rebuilding Poland after the Second World War.

The varying policies of political and cultural repression imposed upon Poland by the three Partitioning Powers inspired differing reactions from the Polish populace. In the first half of the 19th century, there certainly existed a strain of active resistance in the tradition of the rebellions of the Bar Confederates or Tadeusz Kościuszko, most strikingly exemplified in the 1830 and 1863 Uprisings in the Russian Partition.

Meanwhile, others sought to work within the given system of their new rulers, such as Adam Czartoryski (Russia) or Antoni Radziwiłł (Prussia) prior to 1830, or the Polish-Galician nobles (Austria) in the late 19th century. Conversely, many Poles decided that resistance was futile and endlessly frustrating, ultimately assimilating into the new ruling cultures, going as far as converting to Orthodoxy or Protestantism and abandoning Polish as their mother tongue to get ahead in their new social and economic realities.

When political change seemed most unlikely, Polish patriots turned their attention to religion, practical education, economic development, and the preservation and growth of the arts and high culture. Remarkably, Polish culture flourished in the 19th century like almost never before.

Following the wider European trend of “Romanticism” in the arts, Polish poets, novelists, painters, and composers would emphasize universal themes of patriotism and longing for lost love in the particular context of their love for their lost Polish homeland.

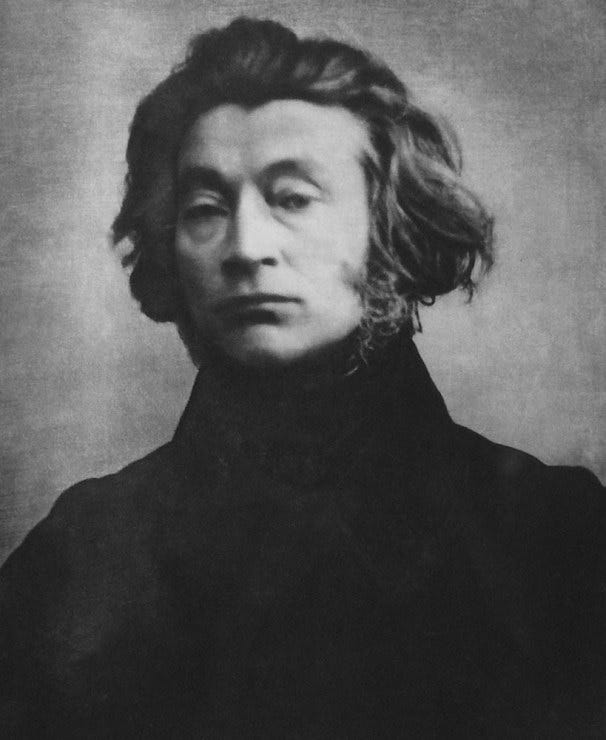

Among the great Polish literary figures of the era were the Romantic “Three Bards” of the early century – Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, and Zygmunt Krasiński – their contemporary, Cyprian Kamil Norwid, and several novelists of the late century, including Henryk Sienkiewicz, Bolesław Prus, Władysław Reymont, and Stanisław Wyspiański.

One could also include among them a certain Józef Konrad Korzeniowski – Joseph Conrad – who was born and raised in the Russian Partition before emigrating to Britain and becoming one of the greatest novelists of the English language.

Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz, a long epic poem idealizing szlachta life in rural Lithuania, was perhaps emblematic of a Polish Romantic culture imagining a better past in light of a miserable present reality. Further elaborating upon this theme was Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy of epic historical fiction novels memorializing the disastrous Polish wars of the mid-17th century that had eclipsed the Commonwealth’s peak period of power and prestige.

As for music, the Poles produced arguably their greatest ever artist in the person of pianist and composer, Fryderyk Chopin, whose piano works are universally regarded as among the most beautiful musical compositions ever written. Also notable was Stanisław Moniuszko, a composer primarily of operas with patriotic themes.

As for the visual arts, painters Jan Matejko and Juliusz Kossak took the lead in capturing on canvass countless memorable episodes from the Polish past in vivid and moving images for the inspiration of languishing patriots.

Finally, in the realm of science, Marie Skłodowska-Curie would remarkably be the first and only person to win a Nobel Prize in two different fields – chemistry and physics – discovering the radioactive elements of Radium and Polonium, the latter of which she named after her native Poland.

It is to the great credit of countless brave and resilient Poles throughout the 19th century that far from being extinguished like her political body, Poland’s cultural soul was both well-preserved and even expanded over the course of the Partition era, inspiring new generations of Poles who had no living memory of the Commonwealth to continue the cultural life of Poland and advocate for the future restoration of her political freedom and independence the moment when the opportunity finally arose.